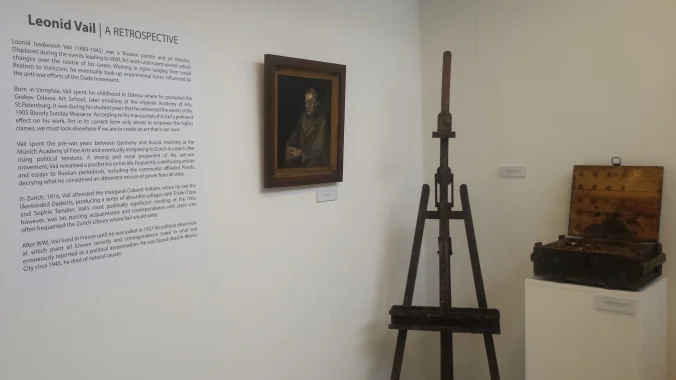

Leonid Isaakovich Vail (1883-1945) was a Russian painter and art theorist. Displaced during the events leading to WWI, his work underwent several radical changes over the course of his career. Working in styles ranging from Social Realism to Constructivism, he eventually took up experimental forms influenced by the anti-war efforts of the Dada movement.

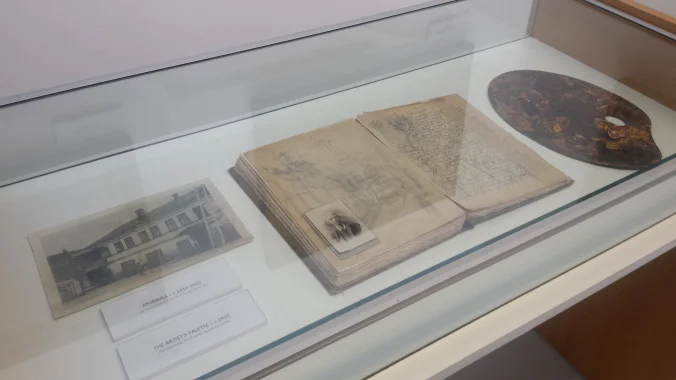

Born in Vinnytsia, Vail spent his childhood in Odessa where he graduated the Grekov Odessa Art School, later enrolling at the Imperial Academy of Arts, St. Petersburg. It was during his student years that he witnessed the events of the 1905 Bloody Sunday Massacre. According to his manuscripts he had a profound effect on his work, ‘Art in its current form only serves to empower the higher classes, we must look elsewhere if we are to create an art that is our own’.

Vail spent the pre-war years between Germany and Russia, teaching at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts and eventually emigrating to Zurich in order to flee rising political tensions. A strong and vocal proponent of the anti-war movement, Vail remained a pacifist his entire life, frequently contributing articles and essays to Russian periodicals, among these the communist affiliated Pravda, decrying what he considered an abhorrent misuse of power from all sides.

In Zurich, 1916, Vail attended the inaugural Cabaret Voltaire, where he met the likeminded Dadaists, producing a series of absurdist collages with Tristan Tzara and Sophie Taeuber. Vail’s most significant meeting of the time, however, was his passing acquaintance and correspondence with Lenin who often frequented the Zurich Library where Vail would write.

After WWI, Vail lived in France until he was exiled in 1927 for political dissension, at which point all known records and correspondence cease in what was erroneously reported as a political assassination. He was found dead in Mexico City circa 1945, he died of natural causes.

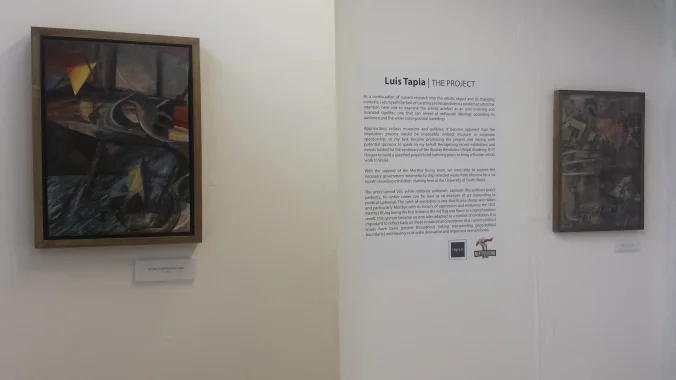

The Project: As a continuation of current research into the artistic object and its changing contexts, I set myself the task of exhibiting a retrospective to a modernist artist; the intention here was to examine the artistic artefact as an ever evolving and nuanced signifier, one that can reveal of obfuscate ideology according to audience and the wider socio-political backdrop.

Approaching various museums and galleries, it became apparent that the requisition process would be impossible without museum or corporate sponsorship, so my task became promoting the project and liaising with potential sponsors to speak on my behalf. Recognising recent exhibitions and events hosted for the centenary of the Russian Revolution (Royal Academy, R17) I began to build a specified project brief outlining plans to bring a Russian artist’s work to Wales.

With the support of the Merthyr Rising team, we were able to acquire the necessary government indemnity to ship selected works from Moscow for a six month travelling exhibition, starting here at the University of South Wales.

The artist Leonid Vail, while relatively unknown, captures this political praxis perfectly, his entire career can be seen as an example of art responding to political upheaval. It is important to reflect back on these instances and recognise that current political issues have been present throughout history, transcending geographical boundaries and leaving in its wake innovative and important new art forms.